Family gatherings at the holidays can be the extremes – familiar and happy, tense and chaotic – and sometimes can be the perfect storm of emotions, conversations and good intentions gone horribly wrong. TapGenes asked health communication expert, Dr. Elissa Foster, professor and author of Communicating at End of Life, for guidance on how to begin talks with our families about the most important topics during the best, loudest and most intense of times. Here’s what Dr. Foster told TapGenes about navigating tough family talks.

Family gatherings at the holidays can be the extremes – familiar and happy, tense and chaotic – and sometimes can be the perfect storm of emotions, conversations and good intentions gone horribly wrong. TapGenes asked health communication expert, Dr. Elissa Foster, professor and author of Communicating at End of Life, for guidance on how to begin talks with our families about the most important topics during the best, loudest and most intense of times. Here’s what Dr. Foster told TapGenes about navigating tough family talks.

Q: How do I start a conversation about my family health history?

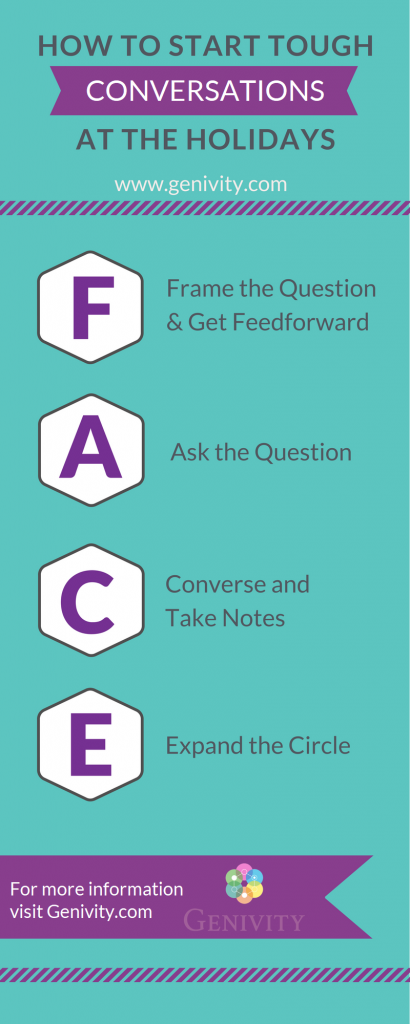

A: FACE to face.

Holiday season is the time of year when the Conversation Project encourages families to initiate discussions about their wishes for end of life care, so that families can be prepared in advance of a life-threatening event. Behind the Conversation Project holiday season campaign is the idea that these difficult health conversations are best when families are together, face-to-face. It’s also true that end of life conversations are not the only ones that benefit from the personal touch. If your family is like most, you don’t typically discuss medical conditions, past illnesses, or relatives’ health unless there is a current crisis that needs attention. Even when the subject is raised, most families tend to share very little about the medical condition itself, preferring to focus on the emotional and practical effects of the illness. Although it is common for families to avoid conversations about health—even good health—the result is that we do not have access to information that can help us to prepare for health changes of our loved ones or to anticipate our potential health needs in the future.

What if you recognize that it’s important to learn more about your family health history, but you don’t know where to start? I’ve developed FACE approach to help you.

Begin by identifying the best person in your family to talk to first—this may be the person who has the most relevant health history for your own information (such as a parent) or it may be the person who serves as the “family historian” by holding the family stories (such as a sister or an aunt). Whomever you choose, it is best if you feel somewhat comfortable raising the subject with them. Find an opportunity to be together, face-to-face, and the following script can guide you through the rest of the conversation. Of course, the content of the conversation will be unique to your family story, but if you can accomplish each of the following steps, you will be well on your way to gathering a clearer picture of you and your family’s health.

Here is what FACE stands for and how to use it to simply and calmly start hard conversations about health.

F – Framing and Feedforward

When broaching a potentially sensitive topic such as health and illness, the first step is the hardest. When you imagine that this conversation might seem to come out of the blue for the person you’re speaking with, sharing your reasons for wanting to talk will be key to the success of your conversation. Sharing your purpose for communicating before launching into the subject is called framing or feedforward (the reverse of feedback). Try to recall what started you thinking about your family’s health history, and begin your conversation by sharing that with your family member. You might say something like this: “Mom, my doctor and I have been discussing whether I should have a mammogram this year, and I realized that I’d never asked you about your experiences with breast health.” Or, “Dad, I was thinking the other day about the stent you had placed in your heart about ten years ago now and I could not remember why you went to the doctor in the first place.” Or, “Aunt Sue, I came across a picture of Grandma the other day and it made me think about the time I was a kid and she was in the hospital for a long time but I didn’t know why.” Whatever the story is, sharing it with your family member will help them to orient themselves and prepare them for the conversation.A – Asking the question

Timing and the willingness of your family member to talk about the topic are essential for success, so this step is when you invite them to participate in the conversation. You may choose to keep the focus of the discussion narrowly on the topic that got you started (like breast health, heart health, and so on) or you can bridge to a larger discussion about family health. For a more focused conversation, follow up your framing/feedforward statement with something like this:- “Is it OK if I ask you some questions about your experience with breast exams?”

- “Can you tell me more about what was happening with your health when your doctor recommended the stress test that led to your heart surgery?”

C – Conversing (and Taking Notes)

Although you are seeking information from your family member, you do not want the experience to feel like an interrogation. Just as you want to the initial question to serve as an invitation, you want the interaction that follows to feel like a conversation. Two principles will help you here:- Take the lead of the person you are speaking with. If they seem interested in telling you a story that seems to take you a little off the path of health history, go with it. By the time the story is finished or even when you reflect on the story later, you may find tremendous relevance that may not be immediately apparent.

- Use the “statement-question” format to keep the conversation going. When your family member says something that requires more information or clarification, restate what you heard them say and then ask the question. For example, “I notice that you’ve mentioned Grandpa’s heart condition a few times. Was that high blood pressure or did he have a type of heart disease or was it something else?”

E – Expanding the Circle

Inevitably, there will be gaps in the stories shared by the first people you speak with—missing facts and questions left unanswered—so it will be important to expand the circle of people included in the discussion. Rounding off this initial conversation with your family member should include three things:- an expression of gratitude (for example, “This has been really helpful to me,” “You’ve helped to answer some questions that were troubling me; thank you.”)

- an indication that you hope the conversation will continue (like, “Please let me know if you remember anything else that may be relevant.”)

- and a request for suggestions of who else to include in the conversation (such as “Who else in the family should I talk to about this?” “Would Uncle Dan know more? Would he be willing to talk with me about it?”).

At some point, these family health conversations may expand naturally so that others are drawn to them, and this is ideal in many ways because the family as a group becomes invested in thinking and talking about the health of its members. When this happens, it will be time to suggest documentation of the family’s health history and suggest ways that such documentation can help existing family members in addition to supporting the health of the next generation. And isn’t that a purpose we can all relate to, particularly at the holidays?

_____

At some point, these family health conversations may expand naturally so that others are drawn to them, and this is ideal in many ways because the family as a group becomes invested in thinking and talking about the health of its members. When this happens, it will be time to suggest documentation of the family’s health history and suggest ways that such documentation can help existing family members in addition to supporting the health of the next generation. And isn’t that a purpose we can all relate to, particularly at the holidays?

_____

Foster